Mitral Valve Prolapse

Mitral (MI-tral) valve prolapse (MVP) is a condition in which one of the heart’s valves, the mitral valve, doesn’t work properly. The flaps of the valve are “floppy” and don’t close tightly.

Much of the time, MVP doesn’t cause any problems. Rarely, blood can leak the wrong way through the floppy valve, which may cause shortness of breath, palpitations (strong or rapid heartbeats), chest pain, and other symptoms.

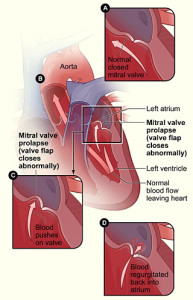

Normal Mitral Valve

The mitral valve controls the flow of blood between the two chambers on the left side of the heart. The two chambers are the left atrium (AY-tree-um) and the left ventricle (VEN-trih-kul).

The mitral valve allows blood to flow from the left atrium to the left ventricle, but not back the other way. (The heart also has a right atrium and ventricle, separated by the tricuspid (tri-CUSS-pid) valve.)

At the beginning of a heartbeat, the atria contract and push blood through to the ventricles. The flaps of the mitral and tricuspid valves swing open to let the blood through. Then, the ventricles contract to pump the blood out of the heart.

When the ventricles contract, the flaps of the mitral and tricuspid valves swing shut. They form a tight seal that prevents blood from flowing back into the atria.

Figure A shows a normal mitral valve that separates the left atrium from the left ventricle. Figure B shows a heart with mitral valve prolapse. Figure C shows the detail of mitral valve prolapse. Figure D shows a mitral valve that allows blood to flow backward into the left atrium.

Mitral Valve Prolapse

In MVP, when the left ventricle contracts, one or both flaps of the mitral valve flop or bulge back (prolapse) into the left atrium. This can prevent the valve from forming a tight seal.

As a result, blood may flow backward from the ventricle into the atrium. The backflow of blood is called regurgitation (re-GUR-ji-TA-shun).

Backflow doesn’t occur in all cases of MVP. In fact, most people who have MVP don’t have backflow and never have any symptoms or complications. In these people, even though the valve flaps prolapse, the valve still can form a tight seal.

When backflow does occur, it can cause symptoms and complications such as shortness of breath, arrhythmias (ah-RITH-me-ahs), or chest pain. Arrhythmias are problems with the rate or rhythm of the heartbeat.

Backflow can get worse over time. It can lead to changes in the heart’s size and higher pressures in the left atrium and lungs. Backflow also increases the risk for heart valve infections.

Now, diagnosing MVP is more precise because of a test called echocardiography (EK-o-kar-de-OG-ra-fee). This test allows doctors to easily identify true MVP and detect troublesome backflow.

As a result, it’s now believed that less than 3 percent of the population actually has true MVP, and an even smaller percentage has serious complications from it.

Medicines can treat troublesome MVP symptoms and prevent complications. Some people will need surgery to repair or replace their mitral valves.

MVP was once thought to affect as much as 5 to 15 percent of the population. It’s now believed that many people who were diagnosed with MVP in the past didn’t actually have an abnormal mitral valve.

They may have had a slight bulging of the valve flaps due to other conditions, such as dehydration or a small heart. However, their valves were normal, and there was little or no backflow of blood through their valves.

Outlook

Most people who have MVP have no symptoms or medical problems and don’t need treatment. These people are able to lead normal, active lives; they may not even know they have the condition.

A small number of people who have MVP may need medicines to relieve their symptoms. Very few people who have MVP need heart valve surgery to repair their mitral valves.

Rarely, MVP can cause complications such as arrhythmias (irregular heartbeats) or infective endocarditis (EN-do-kar-DI-tis). Endocarditis is an infection of the inner lining of the heart chambers and valves. Bacteria that enter the bloodstream can cause the infection.

Signs and Symptoms of Mitral Valve Prolapse

Most people who have mitral valve prolapse (MVP) aren’t affected by the condition. This is because they don’t have any symptoms or major mitral valve backflow.

Among those who do have symptoms, palpitations (strong or rapid heartbeats) are reported most often. Other symptoms include shortness of breath, cough, dizziness, fatigue (tiredness), anxiety, migraine headaches, and chest discomfort.

MVP symptoms can vary from one person to another. They tend to be mild but can worsen over time, mainly when complications occur.

Mitral Valve Prolapse Complications

Complications of MVP are rare. When present, they’re most often due to the backflow of blood through the mitral valve.

Mitral valve backflow is most common among men and people who have high blood pressure. People who have severe cases of backflow may need valve surgery to prevent complications.

Mitral valve backflow causes blood to flow backward from the left ventricle into the left atrium. Blood can even back up from the atrium into the lungs, causing shortness of breath.

The backflow of blood puts a strain on the muscles of both the atrium and the ventricle. Over time, the strain can lead to arrhythmias. Backflow also increases the risk of infective endocarditis (IE), an infection of the inner lining of your heart chambers and valves.

Arrhythmias

Mitral valve backflow can cause arrhythmias. Arrhythmias are problems with the rate or rhythm of the heartbeat.

There are many types of arrhythmia. The most common arrhythmias are harmless. Others can be serious or even life threatening.

When the heart rate is too slow, too fast, or irregular, the heart may not be able to pump enough blood to the body. Lack of blood flow can damage the brain, heart, and other organs.

One troublesome arrhythmia that MVP can cause is atrial fibrillation (AF). In AF, the walls of the atria quiver instead of beating normally. As a result, the atria aren’t able to pump blood into the ventricles the way they should.

AF is bothersome but rarely life-threatening unless the atria contract very fast or blood clots form in the atria. Blood clots can occur because of some of the blood “pools” in the atria instead of flowing into the ventricles. If a blood clot breaks off and goes into the bloodstream, it can reach the brain and cause a stroke.

Infection of the Mitral Valve

A deformed mitral valve flap attracts bacteria that may be in the bloodstream. The bacteria attach to the valve and can cause a serious infection called infective endocarditis (IE). Signs and symptoms of a bacterial infection include fever, chills, body aches, or headaches.

IE doesn’t happen often, but when it does, it’s serious. MVP is the most common heart condition that puts people at risk for this infection.

You can take steps to prevent this infection. Floss and brush your teeth regularly. Gum infections and tooth decay can cause IE.

Diagnosis

Mitral valve prolapse (MVP) most often is found during a routine physical exam when your doctor uses a stethoscope to listen to your heart.

Your doctor listens for a certain “click” and/or murmur. Stretched valve flaps, as seen in MVP, can make a clicking sound as they shut. If the valve is leaking blood back into the atrium, a murmur or whooshing sound often can be heard.

However, these abnormal heart sounds may come and go. Thus, your doctor may not hear them at the time of an exam, even if you have MVP. As a result, you also may have diagnostic tests and procedures to diagnose MVP.

Diagnostic Tests and Procedures

Echocardiography

Echocardiography (echo) is the most useful test for diagnosing MVP. This painless test uses sound waves to create a moving picture of your heart. An echo provides information about the size and shape of your heart and how well your heart chambers and valves are working.

The test also can identify areas of the heart muscle that aren’t contracting normally due to poor blood flow or injury to the heart muscle. In MVP, an echo is used to look for the prolapse of the mitral valve flaps and for the backflow of blood through the leaky valve.

There are several types of echo, including a stress echo. A stress echo is done before and after a stress test. During a stress test, you exercise or take medicine (given by your doctor) to make your heart work hard and beat fast.

A stress echo usually is done to find out whether you have decreased blood flow to your heart (a sign of coronary heart disease, also called coronary artery disease).

An echo also can be done by placing a tiny probe down your esophagus to get a closer look at the mitral valve. The esophagus is the passage leading from your mouth to your stomach.

The probe takes sound wave pictures of your heart. This form of echo is called a transesophageal (tranz-ih-sof-uh-JEE-ul) echocardiogram, or TEE.

Doppler Ultrasound

A Doppler ultrasound is part of an echo test. A Doppler ultrasound is used to show the speed and direction of blood flow through the mitral valve.

Other Tests

Other tests that can help diagnose MVP are:

- A chest x-ray. This test is used to look for fluid in your lungs or to see whether your heart is enlarged.

- An EKG (electrocardiogram). An EKG is a simple test that records your heart’s electrical activity. An EKG can show how fast your heart is beating, whether its rhythm is steady or irregular, and the strength and timing of electrical signals as they pass through your heart

Treatment of Mitral Valve Prolapse

Most people who have mitral valve prolapse (MVP) don’t need treatment because they don’t have complications and have few or no symptoms. Even people who do have symptoms may not need treatment.

The presence of symptoms doesn’t always mean that the backflow of blood through the valve is significant.

People who have MVP and troublesome mitral valve backflow usually need treatment. MVP is treated with medicines, surgery, or both.

The goals of treating MVP include:

- Preventing infective endocarditis (IE), arrhythmias, and other complications

- Relieving symptoms

- Correcting the underlying mitral valve problem, when necessary

Medicines

Medicines called beta blockers have been used to treat symptoms such as palpitations (strong or rapid heartbeats) and chest discomfort in people who have MVP and little or no mitral valve backflow.

If you have MVP and significant backflow and symptoms, your doctor may prescribe:

- Vasodilators to widen your blood vessels and reduce the workload of your heart. Examples of vasodilators are isosorbide dinitrate and hydralazine.

- Digoxin to strengthen your heartbeat.

- Diuretics (water pills) to remove excess fluid in your lungs.

- Medicines such as flecainide and procainamide to regulate your heart rhythms.

- Blood-thinning medicines to reduce the risk of blood clots forming if you have atrial fibrillation. Examples of blood-thinning medicines include aspirin and warfarin.

Surgery

Surgery on the mitral valve is done only when the valve is very abnormal and blood is flowing back into the atrium. The main goal of surgery is to improve symptoms and reduce the risk of heart failure.

The timing of the surgery is very important. If it’s done too early and your leaking valve is working fairly well, you may be put at needless risk from surgery. If it’s done too late, heart damage may have already occurred that can’t be fixed.

Surgical Approaches

Traditionally, mitral valve repair and replacement are done by making an incision (cut) in the breastbone and exposing the heart.

A small but growing number of heart surgeons are using another approach that uses one or smaller cuts through the side of the chest wall. This results in less cutting, reduced blood loss, and a shorter hospital stay. However, this approach isn’t yet available in all hospitals.

Valve Repair and Valve Replacement

In mitral valve surgery, the valve is repaired or replaced completely. Valve repair is preferred when possible. Repair is less likely to weaken the heart. It also lowers the risk of infection and decreases the need for lifelong use of blood-thinning medicines.

If repair isn’t an option, then the valve can be replaced. Mechanical valves and biological valves are available as replacement valves.

Mechanical valves are man-made and can last a lifetime. People who have mechanical valves must take blood-thinning medicines for the rest of their lives.

Biological valves are taken from cows or pigs or made from human tissue. Many people who have biological valves don’t need to take blood-thinning medicines for the rest of their lives. The major drawback of biological valves is that they weaken and often only last about 10 years.

After surgery, a patient usually stays in the intensive care unit in the hospital for 2 to 3 days. Overall, most people spend about 1 to 2 weeks in the hospital. Complete recovery takes a few weeks to several months, depending on your health before surgery.

If you’ve had valve repair or replacement, you may need antibiotics before dental work and surgery that can allow bacteria into the bloodstream. These medicines can help prevent IE, a serious heart valve infection. Discuss with your doctor whether you need to take antibiotics before such procedures.

Experimental Approaches

Some researchers are testing the repair of leaky valves using a catheter (tube) inserted through a large blood vessel.

Although this approach is less invasive and can prevent a patient from having open-heart surgery, it’s only being done at a few medical centers. Large studies haven’t yet shown that this new approach is better than traditional approaches.